Meet Steve Easton, the man who saved Mitchell taxpayers millions

By Megan Luther

It’s a quiet June morning at Mitchell High School. Students are gone and just a handful of staff remain to deep clean rooms or finalize paperwork. In walks a celebrity.

“It’s Steve!” someone shouts from the front office.

As he walks the halls, some do a double-take. Others walk up and shake his hand.

“Howdy stranger,” Steve Easton greets long-time teacher and coach Kent VanOverschelde.

“How are you?”

“Not bad.”

“You know, you skipped out of here without saying goodbye last year.”

“Well, that’s kinda like me.”

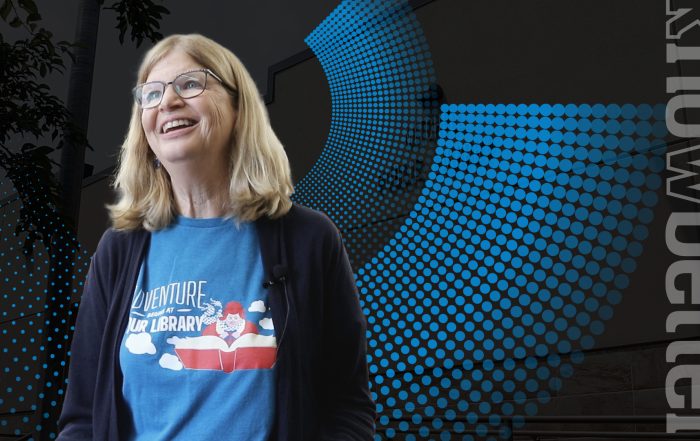

Indeed, Steve lacks the ego or the attention-seeking tendencies of a celebrity. There’s no fake smile under his graying mustache. He doesn’t even like having his picture taken.

But for more than 30 years he played a vital role at Mitchell High School. As maintenance foreman, he made the building functional, comfortable even, which is a hard task with a 62-year-old school.

Taxpayers surely owe him a thank you. Steve kept MHS going well past its prime, most certainly staving off for years the big expense of a new school.

Jack of all trades

Nearly four decades ago, a relative told Steve about the high school job. Steve knew the building well as a student in the seventies. After a decade working construction out of town, Steve was sick of traveling, but he still enjoyed that type of work: electrical, plumbing, construction and cars. “So it kind of fit my job expertise, I guess you could say.”

There’s no manual or YouTube video on how to run such a building. Those ins and outs are stored in Steve’s head. It’s knowledge he gained through what he calls trial and error.

“Jack of all trades. Master of a few,” he admits.

He’s underselling himself, of course.

“Maintaining an older building is no small feat. It’s a task that demands not only technical expertise but also a deep commitment to the institution,” said Don Gilpin, President and CEO, IFMA, the world’s largest association for facility management professionals.

It’s a job that would drive those who need routine nuts. Steve could plan his day, but inevitably, something would break and many times, in hard-to-reach places. To access the pipes for heating, cooling and electrical, Steve had to snake his way through the tunnels beneath the school, most so small, he had to crawl.

Truly, no one knows all 165,000 square feet of the high school better than Steve.

“If you’re wondering why there was a pipe in the wall in room 113 that didn’t go to anything. You could ask Steve and he knew exactly what the situation was and why it was there and why it needed to be there and every other detail,” says Mitchell School Superintendent Joe Childs.

Eventually, Steve became psychic. Before the clouds even opened up, he placed buckets where he knew rain would leak through. On humid nights, he stood by, ready to drive five miles from his house to shut off the touchy school fire alarms.

What many would call a cluster, Steve saw an opportunity to get creative. He loved a challenge and fixing equipment when the parts are no longer made most certainly qualified. This went beyond putting lipstick on a pig. In recent years, Steve had to figure out how to host advanced technology in an antiquated building.

But Steve rarely rattled. In fact, his colleagues couldn’t remember a time he lost his cool, even when dealing with vandals. “Instead of being frustrated, instead of being angry, he just always had a cool and calm demeanor every day,” said Craig Mock, the former high school vice principal who worked with Steve for 21 years.

As the years passed and people retired, Steve’s duties grew. His to do list included school vans, the football stadium and Mitchell Career and Technical Education Academy, MCTEA, across the street from the high school.

While not his job (words Steve would never utter), he would even do a load of laundry. “A lot of times I’d throw it in because I’m walking right by there anyhow.”

The man with 37 keys, who greased gears and tightened pipes, also saved prom.

Teacher Lori Schmidt, who just finished her 30th year organizing the high school prom, has called on Steve more than once in the nearly four decades they worked together.

Part of her job is setting up the prom at the Corn Palace. It can be a struggle to get the old school food truck lift down so she can unload prom decorations. “I could never get those damn buttons to work.” So, she called Steve.

“Prom Queen. What’s the matter now?” he would tease.

“It was of course the damn truck,” Lori recalled

“Oh, Queen. I will be right there.”

Steve was always on call. Fire alarms, truck lifts, unbearable heat in the gym. Not sleeping through the night was something Steve was used to, especially during calving season. When he wasn’t at the school, he was tending to up to 100 head of cattle. “Pretty much all my life.”

Is there anything Steve doesn’t do? “I don’t do windows.”

Passing the Torch

Steve had been telling his close colleagues for years, this was his last. But every school year, he’d be there. His bosses even knew retirement was close so in the fall of 2022, Blake Biggerstaff walked in ready to download Steve’s knowledge.

It’s intimidating, filling shoes that walked the same halls for decades. “Actually, I didn’t know if I’d be able to do it,” Blake admitted. But he came prepared. He followed Steve around daily, jotting down everything in his yellow notebook he labeled “The Book of Steve.”

“You know, I didn’t realize how much stuff there was here and how many different things there was to do until I had to actually show Blake,” Steve realized.

Quiet Goodbye

Walking into her classroom last fall, Lori noticed a message on her board. There, in black marker on her white board “Have a good year, Schmidty. -SE”

She cried. “And right then, I knew, oh, it gets to me yet. I knew that he had retired and he was done.”

There was no fanfare. No party. Not even goodbyes.

In true Steve fashion, he quietly walked out of the building last summer. It was time. Steve was getting older and his health not what it used to be. He has children and grandchildren, fish to catch and deer to hunt.

But it’s hard to stay away. He misses the people, his colleagues, the most. Almost a year after his retirement, he walks the halls this June morning, pointing out jury-rigged projects he tackled.

This is the last summer for Mitchell High School, a building that needs to be torn down. Or as Steve politely says, “It’s reached its maturity.”

Its replacement under construction just across the street is expected to be completed in late spring next year.

As Steve takes what is probably his final tour, he walks to the old auditorium, former home to musicals, concerts and school assemblies. Now it’s used for storage. He opens the back door with a spare set of keys he found in his truck the other day.

“I still remember where the light switches are.” Steve flicks, but nothing happens. With his cell phone light in hand, he goes to the light dimmer controls and fiddles around.

“They always turn a breaker off. They’re not supposed to, and it happens to be the one for the light switch.” And it now works. Retired and still fixing things. Steve just can’t help himself.

Megan Luther, a lifelong storyteller, has called Mitchell home for more than 30 years.